Clef Transposition

ADVERTISEMENT

Clef Transposition

The technique of transposing by changing clef is probably the single best technique to

master for the reading of orchestral scores, which typically demand the performance of

multiple, simultaneous transpositions. It requires a considerable amount of practice

before it becomes comfortable, however, and may in fact seem far too cumbersome to be

worthwhile. However, it is definitely a skill which can be acquired, and once practiced,

becomes relatively effortless.

The Basic Technique

A clef-based transposition works by mentally changing the notated clef to some other

clef. As a result, the notation on the staff will now refer to different pitches.

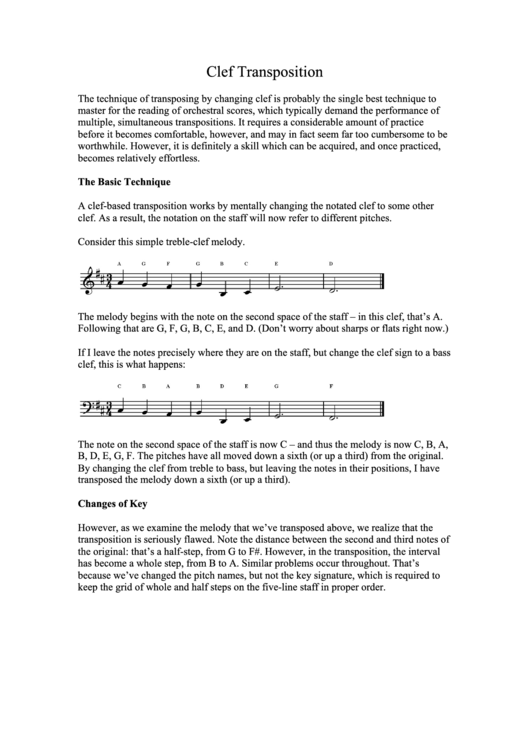

Consider this simple treble-clef melody.

The melody begins with the note on the second space of the staff – in this clef, that’s A.

Following that are G, F, G, B, C, E, and D. (Don’t worry about sharps or flats right now.)

If I leave the notes precisely where they are on the staff, but change the clef sign to a bass

clef, this is what happens:

The note on the second space of the staff is now C – and thus the melody is now C, B, A,

B, D, E, G, F. The pitches have all moved down a sixth (or up a third) from the original.

By changing the clef from treble to bass, but leaving the notes in their positions, I have

transposed the melody down a sixth (or up a third).

Changes of Key

However, as we examine the melody that we’ve transposed above, we realize that the

transposition is seriously flawed. Note the distance between the second and third notes of

the original: that’s a half-step, from G to F#. However, in the transposition, the interval

has become a whole step, from B to A. Similar problems occur throughout. That’s

because we’ve changed the pitch names, but not the key signature, which is required to

keep the grid of whole and half steps on the five-line staff in proper order.

ADVERTISEMENT

0 votes

Related Articles

Related forms

Related Categories

Parent category: Life

1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

5 6

6 7

7