An Example Of An 'A' Paper - History 451

ADVERTISEMENT

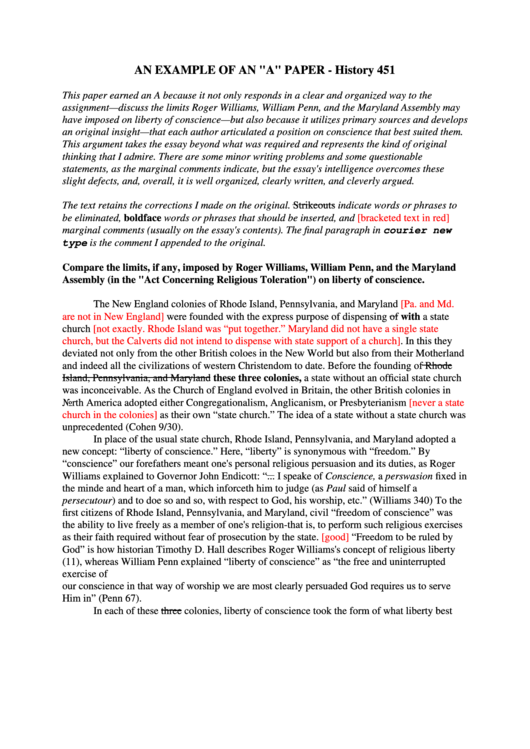

AN EXAMPLE OF AN "A" PAPER - History 451

This paper earned an A because it not only responds in a clear and organized way to the

assignment—discuss the limits Roger Williams, William Penn, and the Maryland Assembly may

have imposed on liberty of conscience—but also because it utilizes primary sources and develops

an original insight—that each author articulated a position on conscience that best suited them.

This argument takes the essay beyond what was required and represents the kind of original

thinking that I admire. There are some minor writing problems and some questionable

statements, as the marginal comments indicate, but the essay's intelligence overcomes these

slight defects, and, overall, it is well organized, clearly written, and cleverly argued.

The text retains the corrections I made on the original. Strikeouts indicate words or phrases to

be eliminated, boldface words or phrases that should be inserted, and

[bracketed text in red]

marginal comments (usually on the essay's contents). The final paragraph in courier new

type is the comment I appended to the original.

Compare the limits, if any, imposed by Roger Williams, William Penn, and the Maryland

Assembly (in the "Act Concerning Religious Toleration") on liberty of conscience.

The New England colonies of Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, and Maryland

[Pa. and Md.

are not in New England]

were founded with the express purpose of dispensing of with a state

church

[not exactly. Rhode Island was “put together.” Maryland did not have a single state

church, but the Calverts did not intend to dispense with state support of a

church]. In this they

deviated not only from the other British coloes in the New World but also from their Motherland

and indeed all the civilizations of western Christendom to date. Before the founding of Rhode

Island, Pennsylvania, and Maryland these three colonies, a state without an official state church

was inconceivable. As the Church of England evolved in Britain, the other British colonies in

North America adopted either Congregationalism, Anglicanism, or Presbyterianism

[never a state

church in the colonies]

as their own “state church.” The idea of a state without a state church was

unprecedented (Cohen 9/30).

In place of the usual state church, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, and Maryland adopted a

new concept: “liberty of conscience.” Here, “liberty” is synonymous with “freedom.” By

“conscience” our forefathers meant one's personal religious persuasion and its duties, as Roger

Williams explained to Governor John Endicott: “... I speake of Conscience, a perswasion fixed in

the minde and heart of a man, which inforceth him to judge (as Paul said of himself a

persecutour) and to doe so and so, with respect to God, his worship, etc.” (Williams 340) To the

first citizens of Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, and Maryland, civil “freedom of conscience” was

the ability to live freely as a member of one's religion-that is, to perform such religious exercises

as their faith required without fear of prosecution by the state.

[good]

“Freedom to be ruled by

God” is how historian Timothy D. Hall describes Roger Williams's concept of religious liberty

(11), whereas William Penn explained “liberty of conscience” as “the free and uninterrupted

exercise of

our conscience in that way of worship we are most clearly persuaded God requires us to serve

Him in” (Penn 67).

In each of these three colonies, liberty of conscience took the form of what liberty best

ADVERTISEMENT

0 votes

Related Articles

Related forms

Related Categories

Parent category: Education

1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4